Israel in the Time of the Egyptian New Kingdom

Upper and Lower Egypt

The Egyptian New Kingdom began with the reunification of Upper and Lower Egypt under the 18th Dynasty Pharaoh Ahmose (c. 1540 BC). The New Kingdom period extended through the 19th– (1295–1186 BC) and the 20th Dynasties (1186–1070 BC). It was in the New Kingdom period that Egypt became an empire (c. 1457 BC), gaining sovereignty north to Syria and south into Nubia. Throughout this time Israel was enslavement in the eastern Delta of Egypt.

At the close of the Late Bronze Age (c. 1200 BC) the empire began to collapse, and Egypt progressively withdrew to its own borders, abandoning Canaan by c. 1140 BC.

At no time prior to this date (c. 1140 BC) could the Israelites have invaded and occupied Canaan consistent with the biblical text, the archaeological evidence, and known Egyptian presence and policies in Canaan—as this article will show.

Key Dates in the 12th Century BC Chronology: Abram went down to Egypt for a brief sojourn sometime after c. 1715 BC. Jacob and his offspring entered Egypt c. 1600 BC. The Israelites were enslaved in the Egyptian Delta thirty years later, c. 1570, and departed Egypt 400 years after that, c. 1175 BC. They endured 40 years in the northern Sinai wilderness and invaded Canaan c. 1135 BC. The period of the Judges began c. 1130 BC.

The Israelites Went Down to Egypt

Abram did what other pastoral seminomads east and north of Egypt did in the second millennium BC (and before) in times of drought; he took his animals via the Way or Shur and petitioned the Egyptians for entry to the Wadi Tumilat (known as Tjeku and Goshen), an ancient eastern distributary of the Nile that flowed east to the Isthmus of Sinai.

In the Land of Goshen (the Wadi Tumilat)

This 35-mile-long, low-lying depression retained Nile waters after the annual inundation. This produced a constantly verdant region of pasturage available to herdsmen during frequent droughts in southern Canaan and the Transjordan. This frontier region was defended on the east by a system called the Walls of the Ruler. Entry and exit from this region was controlled by Egyptian military forces.

The Eastern Delta – a Land of Swamp

Two capitals (Avaris and Rameses/Raamses) existed on the Pelusiac Branch of the Nile in the Egyptian Delta in the dynastic period. East of the Pelusiac branch, the terrain was a vast swamp of no use for agricultural purposes. However, the narrow tract of the Wadi Tumilat was ideal for the forage of flocks and herds.

Shasu tribesmen (that would have included the Israelites) could normally expect Egyptian clearance to enter and depart this region. This arrangement offered several advantages for the Egyptians. Pastoralists provided animal products for the Egyptian markets; they could work as seasonal laborers and were customers for products sold in the Egyptian markets. This arrangement also defused potential violence and the wanton depredations of tribesmen in the Delta that had occurred before the construction of the Walls of the Ruler (which began c. 1795 BC) along the east Delta frontier. In addition to providing military defense of the Delta, the Walls provided security for Egyptian farms and towns.

The entry to the Wadi Tumilat (the Way of Shur) was the southern of two ways into the Delta. The main entry was 30 miles north , along the coast, known the Ways of Horus. There were no other negotiable routes into or out of the Delta from the east.

Avaris: Capital of the 14th- and 15th Dynasties of Lower Egypt

Abram entered Egypt in the time of the 14th Dynasty (c. 1710 BC), when the capital of Lower Egypt was at Avaris, 15-20 miles north of the likely Israelite encampment in the Wadi Tumilat.

Jacob and his offspring entered the Delta a century later (c. 1600 BC) in the time of the 15th Dynasty (ruled by Asiatic Amorites, not Egyptians). The 15th Dynasty’s capital of Lower Egypt was also at Avaris (Tell el-Daba).

In both periods Egypt was divided into competing regimes occupying Upper Egypt (the Nile River south of the Delta) and Lower Egypt (the Delta).

Israelite entry into Egypt via the Wadi Tumilat (Goshen). The capital of Lower Egypt was Avaris in the time of Abram and Jacob

Israelite entry into Egypt via the Wadi Tumilat (Goshen).

Prisoners of War c. 1570 BC

The 12th century BC chronology envisions Jacob’s entry into Egypt c. 1600 BC during the Hyksos period. He and his people were caught in the crossfire of a dynastic struggle and were enslaved c. 1570 BC. The 17th Dynasty (that became the 18th Dynasty) rose to power far upriver at Thebes. Their efforts to overthrow the Hyksos 15th Dynasty in the Delta resulted in territorial gains south of Avaris, including the Wadi Tumilat where the Israelite were sojourning. The Israelites became spoils of war.

The enslavement of the small Israelite enclave (of perhaps several hundred people) occurred decades before the last Hyksos defenders of Avaris capitulated and departed Egypt, c. 1540 BC.

There is no record of the fortunes of the enslaved Israelites from c. 1570 BC until 300 years later (c. 1270 BC) in the time of the Oppression described in Exod. 1.

The Israelites Went Down to Egypt

Abram did what other pastoral seminomads east and north of Egypt did in the second millennium BC (and before) in times of drought; he took his animals via the Way or Shur and petitioned the Egyptians for entry to the Wadi Tumilat (known as Tjeku and Goshen), an ancient eastern distributary of the Nile that flowed east to the Isthmus of Sinai.

In the Land of Goshen (the Wadi Tumilat)

This 35-mile-long, low-lying depression retained Nile waters after the annual inundation. This produced a constantly verdant region of pasturage available to herdsmen during frequent droughts in southern Canaan and the Transjordan. This frontier region was defended on the east by a system called the Walls of the Ruler. Entry and exit from this region was controlled by Egyptian military forces.

Israelite entry into Egypt via the Wadi Tumilat (Goshen).

The Eastern Delta – a Land of Swamp

Two capitals existed on the Pelusiac Branch of the Nile in the Egyptian Delta in the dynastic period. East of the Pelusiac, the terrain was a vast swamp of no use for agricultural purposes. However, the narrow tract of the Wadi Tumilat was ideal for the forage of flocks and herds.

Shasu tribesmen (that would have included the Israelites) could normally expect clearance from the Egyptians to enter and depart this region upon request. This arrangement offered several advantages for the Egyptians. Pastoralists provided animal products for the Egyptian markets; they could work as seasonal laborers; and they were customers for products sold in the Egyptian markets. This arrangement also defused potential violence and the wanton depredations of tribesmen that had occurred in the Delta before construction of the Walls of the Ruler (began c. 1795 BC) along the east Delta frontier. It was built to ensured the security of Egyptian farms and towns.

The entry to the Wadi Tumilat (the Way of Shur) was the southern of two ways into the Delta. The main northern entry, 30 miles north along the coast, was called the Ways of Horus. There were no other survivable routes into or out of the Delta from the east.

Avaris: Capital of the 14th- and 15th Dynasties of Lower Egypt

Abram entered Egypt in the time of the 14th Dynasty (c. 1710 BC), when the capital of Lower Egypt was at Avaris, 15-20 miles north of the likely Israelite encampment in the Wadi Tumilat.

Jacob and his offspring entered the Delta a century later (c. 1600 BC) in the time of the 15th Dynasty (ruled by Asiatic Amorites, not Egyptians). The 15th Dynasty’s capital of Lower Egypt was also at Avaris (Tell el-Daba).

In both periods Egypt was divided into competing regimes occupying Upper Egypt (the Nile River south of the Delta) and Lower Egypt (the Delta).

Prisoners of War c. 1570 BC

The 12th century BC chronology envisions Jacob’s entry into Egypt c. 1600 BC during the Hyksos period. He and his people were caught in the crossfire of a dynastic struggle and were enslaved c. 1570 BC. The 17th Dynasty (that became the 18th Dynasty) rose to power far upriver at Thebes. Their efforts to overthrow the Hyksos 15th Dynasty in the Delta resulted in territorial gains south of Avaris, including the Wadi Tumilat where the Israelite were sojourning. The Israelites became spoils of war.

The enslavement of the small Israelite enclave (of perhaps several hundred people) occurred decades before the last Hyksos defenders of Avaris capitulated and departed Egypt, c. 1540 BC.

There is no record of the fortunes of the enslaved Israelites from c. 1570 BC until 300 years later (c. 1270 BC) in the time of the Oppression described in Exod. 1.

The Rise of the Egyptian Empire: The 18th Dynasty

In c. 1457 BC Thutmose III (1479-1425 BC) of the 18th Dynasty mobilized Egypt’s divisions and marched north to Canaan’s Jezreel Valley to confront and destroy a large enemy coalition that was preparing to advance against Egypt. The spoils of the dramatic engagement introduced a new method of enriching the Egyptians and marked the beginning of the empire.

Thutmose III was depicted as a warrior king, able to fire arrows through thick copper targets from a charging chariot. The perfection of chariot warfare with soldiers employing powerful compound bows transformed the army into a first-rate military force. Thutmose’s son and successor, Amenhotep II (1427–1401 BC), was depicted as the consummate warrior, described as a master of horses and chariot warfare and bold in battle.

From this time Egyptian presence would be felt in Canaan and points north. Following the victory in Canaan, Egyptian troops were garrisoned at key locations in the northern province. The subjugated lands were tasked with tribute not only to support the Egyptian presence but also to sustain Egyptian temples in the homeland and to continuously contribute to the royal coffers. This tribute included agricultural produce, timber, and minerals as well as a steady supply of slaves. Manpower obtained in this way supplemented the large numbers the Egyptians captured in war and those sold into the Egyptian economy. The Egyptian demand for human labor would become ravenous by the time of Ramesses II (1279–1213 BC), Pharaoh of the Oppression.

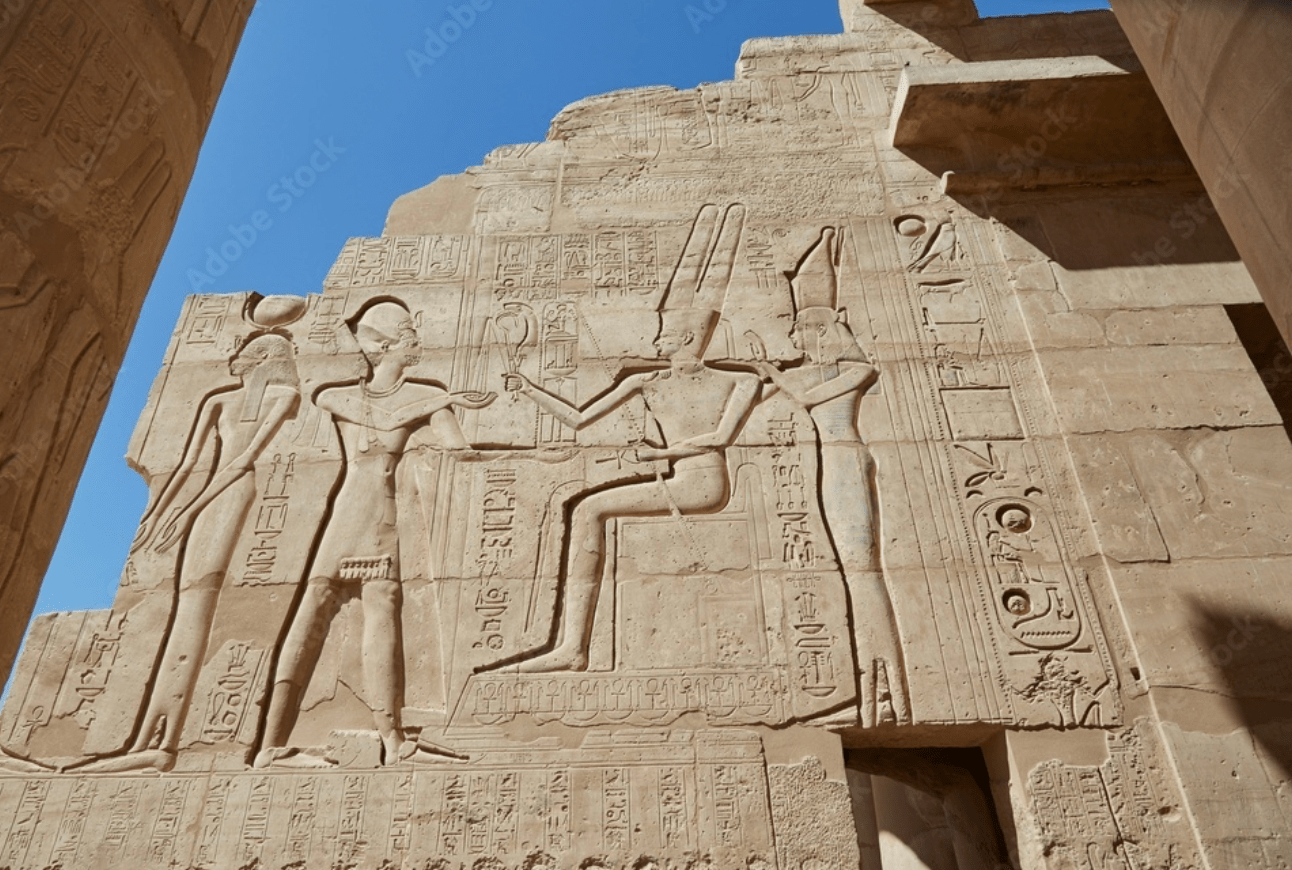

Festival Temple of Thutmosis III (1479–1429 BC) at Karnak. Founder of the Egyptian Empire

Revenues from Canaan

On his second campaign (year 9, c. 1418 BC), Amenhotep II recorded on a stele the capture of 101,128 men along with great wealth and more than 1,000 captured chariots. (These numbers are obviously exaggerated.) Theban tomb scenes during this period depict abundant Asiatic goods brought to Egypt. These goods are referred to as tribute but may have included the products of commerce, gifts, and enforced levies. Counted as the best of the booty of the pharaoh were the children of the princes of the northern vassal states and the southern countries (Nubia). These children filled pharaoh’s workshops and were regarded as gifts of Amon, thus ensuring their acculturation into the Egyptian perspective for when they returned to assume the thrones of their kingdoms.

An Egyptian army officer would periodically appear in towns and villages in Retenu (the northern province) to collect taxes and settle disputes. Failure to comply with levies constituted rebellion that might trigger military action and possible deportation of the local rebellious population. Local kings, princes, and mayors of city-states to the north continued to rule their towns and environs but only at Egypt’s pleasure. To the south of Egypt, below the cataracts, an Egyptian viceroy ruled Nubia, where few towns existed; the viceroy ruled with a primary objective of extracting gold from the wilderness east of the Nile and grain from the harvests along the river. Troops manning large fortresses enforced this status quo.

A core full-time professional Egyptian army, formed during the New Kingdom, was supplemented for major expeditions by conscriptions from among temple communities. The frontiers, north and south, were guarded by soldiers manning fortified garrison towns. Troop strength might have varied at some sites from twenty to several hundred troops serving up to six years. In addition to Egyptians, Nubians, Libyans, Sea Peoples, and later Philistines were recruited to man these fortresses.

The 15th-century BC chronology identifies Thutmose III as the Pharaoh of the Oppression and Amenhotep II as the Pharaoh of the Exodus—probably the least likely regimes in which the Oppression and the Exodus could have occurred, given their military presence in Canaan. (To fit these pharaohs into their chronology, advocates of this chronology must rely on different dynastic dates than used here.)

Fast-forward to the mid-14th century BC, to the time of the heretic pharaoh Akhenaton (1353–1337 BC). Several hundred documents from this pharaoh’s reign illustrate how Egypt maintained an iron grip on Canaan with minimal investment in manpower. They also illustrate why the Israelites could not have been in Canaan in this period.

Israel in the Time of Amarna

1353-1337 BC

In 1887, a Bedouin woman discovered the first of the Amarna Letters (cuneiform clay tablets) in the ruins of an ancient city on the east bank of the Nile, 190 miles south of Cairo. These ruins were the remains of the “Horizon of the Sun’s Disc” (Akhetaten), the capital city built by Pharaoh Akhenaton (1353-1337 BC).

More than 300 recovered Letters from this site represent official correspondence between the Egyptian crown and vassal kingdoms in Canaan and Syria. They are snapshots of the geopolitical realities in Syria-Canaan that form a context against which biblical history can be assessed.

The Letters portray violence and insecurity prevailing in the hill country of Canaan as warlords of such towns as Megiddo, Shechem, Jerusalem, and Gezer struggled against one another for territory. The Letters from these kings plead with Akhenaton for support against their enemies. The picture is one of political fragmentation that facilitated Egyptian control and depict complete domination of the land by Egyptian forces. Conflict between the vassal kings of Canaan insured no single entity could consolidate power to rise in opposition to Pharaoh’s grip on Canaan.

The reign of Akhenaton is sometimes considered a period of lax control of the dominions to the north. There is no solid evidence of this. While Akhenaton may have been preoccupied with his religion and family, the Egyptian military evidently maintained the status quo in Canaan.

Most importantly, there is no mention in the Amarna Letters of any group that can be identified with the biblical Israelites. The geopolitical realities of this period are inconsistent with the Israelites’ biblical presence in Canaan in this period—which is presumed in the 15th century BC chronology. Instead, the Israelites remained as an unheralded and steadily growing population of slaves in Egypt’s Delta. There is no record of them until the rise of the 19th Dynasty and the Pharaoh of the Oppression, Ramesses the Great.

Barry Kemp of Cambridge University excavated the site for more than 35 years. He catalogued 1,150 buildings.

Akhenaton transported 20,000 to 50,000 people to his new city that stretched eight miles along the Nile. Not long after his death, the city was abandoned.

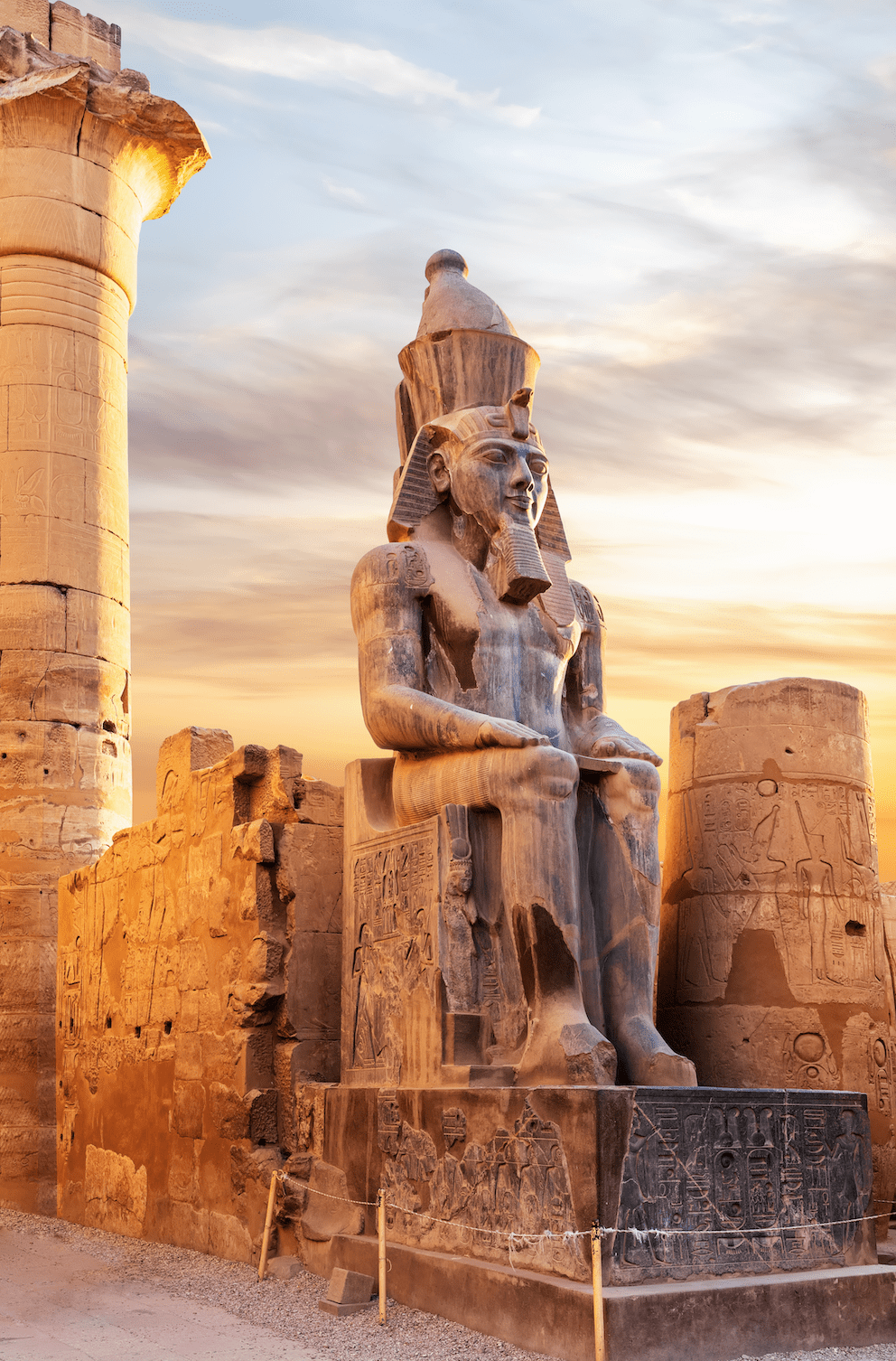

Ramesseum, the Mortuary Temple of Ramesses II

Israel in the Time of the 19th Dynasty

1295 – 1186 BC

There is no reason to assume Egypt’s policies and continuing exploitation of Canaan changed from the time of Akhenaton’s demise (c. 1337 BC) to the rise of the 19th Dynasty that replaced the moribund 18th Theban Dynasty (c. 1295 BC).

The 19th Dynasty produced the greatest of all of Egypt’s pharaohs, Ramesses II (1279–1213 BC), who set out to build his new capital Raamses/Rameses (Pi-Ramesses) in the Egyptian Delta and a fortress city in the Wadi Tumilat, Pithom—two cities Exod. 1:11 says the Israelites were tasked with building.

By deduction, this biblical text (Exod. 1:11) identifies Ramesses II as the Pharaoh of the Oppression, since he was the builder of these cities. Moses was born in this time and grew up in Ramesses’s extended household. Stories of Moses’s preeminence as an heir to the Egyptian crown and a heroic general are bogus, pure inventions found in the works of Josephus. Ramesses, the father of an “army of children,” had at least 45 sons that could succeed him and occupy the highest offices of the land. (Though not a prominent personality within the palaces of Pharaoh, Moses would been extensively trained in languages and scribal skills, qualifying him to have written the Pentateuch.) Reaching maturity Moses killed an Egyptian taskmaster; his deed was found out, and he fled for his life to Midian where he spent a generation before returning to Egypt.

While Moses was in Midian, Ramesses died, and his sixth son, Merenptah (1213–1203 BC), replaced his father. Two notable events occurred in Merenptah’s reign: He defeated the Libyan/Sea People invasion force in the western Delta, and he assaulted the Israelites in retaliation (presumably) for an unsuccessful attempt to escape Egypt—this likely occurred during the war the war against the Libyans in the west of the Delta.

Advocates of the 13th century chronology must claim that the Exodus (as well as the Oppression) occurred in the reign of Ramesses II so that the Israelites could be in Canaan in the time of Merenptah (c. 1208 BC). They believe Merenptah’s claim to have “destroyed the seed of Israel” occurred in the land of Canaan. But this cannot be correct. This issue is discussed below in Objections/Merenptah Stele.

The Exodus in the Time of Ramesses III (1175 BC): The 20th Dynasty

Moses returned to Egypt after the rise of the 20th Dynasty in the time of Ramesses III (1184-1153 BC)—according to the 12th century reconstruction. It was during Ramesses III’s reign that the Israelite Exodus occurred.

In 1177 BC, Ramesses III fought a desperate land and sea battle (likely on his eastern frontier) against the Sea Peoples. This was the culminating event in the collapse of Late Bronze Age civilization in the eastern Mediterranean. Ramesses won this battle but soon lost the last remnants of the empire.

Ramesses III’s mortuary temple (Medinet Habu)

After 1177 BC, the loss of economic partners to the north (whose cities lay in smoking ruins) made security of the International Highway through coastal Canaan less relevant; the land to the north of Egypt was in chaos and overrun with refugees.

Among the Sea Peoples Ramesses III defeated were the Philistines who settled along the southern coastal plain of Canaan (c. 1177 BC). (Their appearance there would be a significant factor in Israel’s history in the time of the Judges leading to the demand for a king like all the other nations.)

Two years after Ramesses III’s repulse of the Sea Peoples, the Israelites successfully departed Egypt c. 1175 BC. The Israelites would not thereafter encounter the Egyptians in the land of Canaan. Ramesses III, Pharaoh of the Exodus, the Pharaoh who defied Yahweh, was to meet an inglorious and impoverished end. He was murdered by his own family in his funerary temple at Medinet Habu across the river from Thebes.

18th Dynasty – BC

Ahmose (1540-1515)

Amenhotep I (1515-1494)

Thutmose I (1494-1482)

Thutmose II (1482–1479)

Hatshepsut (1479-1457)

Thutmose III (1479-1425)

Amenhotep II (1427-1401)

Thutmose IV (1401-1391)

Amenhotep III (1391-1353)

Amenhotep IV (Akhenaton) (1353-1337)

Smenkhkare (1338-1336)

Tutankhamun (1336-1327)

Ay (1327-1323)

19th Dynasty – BC

Ramesses I (1295-1294)

Seti I (1294-1279)

Ramesses II (1279-1213)

Merenptah (1213–1203)

Set II (1200-1194)

Siptah (1194-1188)

Tewosret (1188-1186)

20th Dynasty – BC

Setnakht (1186-1184)

Ramesses III (1184-1153)

Ramesses IV/XI (1153-1070)