The Destruction of Greater Hazor

A second major objection to the 12th century BC Exodus/Conquest chronology is the belief that the Israelites destroyed Greater Hazor c. 1230 BC during the northern campaign of the Conquest recorded in Joshua 11. Principal excavators of the two major expeditions to Hazor have speculated that the Israelites were the perpetrators of this destruction but offer no tangible evidence of this.

They offer this explanation because they have no other candidate. But if this is true—if the Israelites did destroy Greater Hazor—the Conquest would have begun not long before c. 1230 BC, during the reign of Ramesses II (1279–1213 BC).

Why the Israelites could not have destroyed Greater Hazor

- An Israelite invasion in the 13th century does not seem possible given Egypt’s military domination of Canaan

- An Israelite invasion before the latter 12th century is contradicted by the archeological evidence at biblical Conquest sites that did not exist before then

- The Bible does not mention the presence of Egyptians in Canaan during the Conquest which would have been a reality in the latter 13th century BC (in the time or Ramesses II)

- The Bible text identifies the site Joshua destroyed as the former head of all those kingdoms (i.e., NOT Greater Hazor)

Some scholars note…

- The last military campaign of Ramesses into Canaan was c. 1269 BC; there were no known military campaigns into Canaan until the time of Merenptah (just before c. 1208 BC) and . . .

- There is no evidence of an active foreign policy toward Canaan by Ramesses II in his later years, implying (perhaps) that he would not have responded to the Israelite invasion and destruction of Greater Hazor. That does not seem likely for a number of reasons.

This assumes…

- The Egyptians had lost interest in Canaan in the time of Ramesses II

- The Egyptians had ceased to exploit the resources of the province (grain, taxes, manpower)

- Canaan was no longer considered a vital military buffer zone defending Egypt’s northern frontier

- The International Highway through Canaan no longer needed protection

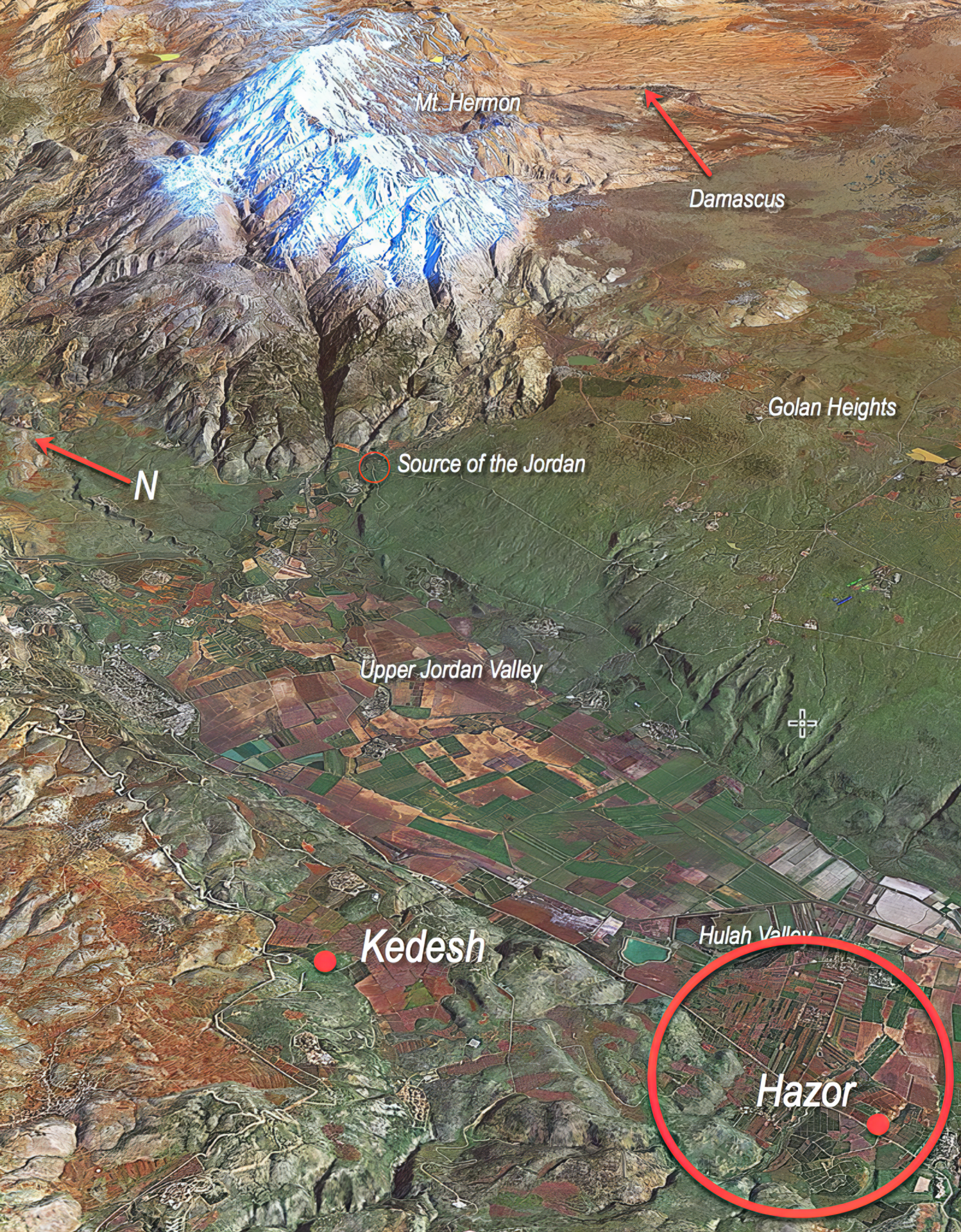

Hazor in the Upper Jordan Valley

(Courtesy RØHR Productions, Ltd.

These assumptions must be wrong because…

- Egyptian military garrisons existed (at various times) at Gaza, Megiddo, Beth-Shean, and at towns such as Deir el-Balah, Tel Mor, Ashkelon, Tel Aphek, Tell es-Saidiyeh, and Joppa (Jaffa)—where the largest Egyptian fortress was located and maintained into the 12th century BC. (Egyptian troops may have been stationed further north in the Beqaa Valley.)

- These military forces would surely have reacted to the Israelite depredations along the coast described in the biblical Conquest account had they occurred in the 13th century BC

- The Egyptians must have continued to exploit the resources of Canaan through the 19th Dynasty; the Israelites would have posed a threat to this revenue stream

- Though peace had been established with Hatti (the most powerful recent enemy north of Egypt), Canaan would have remained a strategic asset as a military buffer zone insuring the security of the International Highway

- It is in this period (latter 13th century BC) that the greatest quantity and variety of types of Egyptian and Egyptian-like materials appear in Canaan

The Destruction of Greater Hazor

There is no known record of Greater Hazor’s destruction in Egyptian documents. And there are no clues within the destruction level that can help identify the perpetrators.[1] It is evident that the strategic importance of Greater Hazor had waned by the time of its destruction since the International Highway to Damascus had been rerouted to the south, bypassing Hazor by the time of the city’s fall. This may be significant.

If the administrative policies of the Amarna period (1353–1337 BC) were typical at the time of Greater Hazor’s destruction, Ramesses II may have been indifferent to the fate of the city, considering it a regional matter. But this does not mean, surely, that he would have tolerated a threat to his sovereignty and economic interests in Canaan.

The biblical account of the Israelite overthrow of the status quo in the highlands, reported raids on Egyptian held towns along the coast, and war in the Jezreel and further north would have represented a serious challenge to Egyptian interests that would not have been tolerated, based on the history of Egypt’s dealings with the province.

Another major consideration (noted several times in above articles) is that the Bible does not mention any encounter with, or reference to, Egyptian presence in Canaan in the time of the Conquest and the period of the Judges.

Greater Hazor included the Upper and Lower Cities of 140 acres. The Hazor of Joshua’s time was likely limited to a small portion of the Upper City of about 15 acres. (Courtesy RØHR Productions, Ltd.)

Here is another important point: Joshua 11:10 specifies that the Hazor Joshua destroyed was formerly the head of that coalition of kingdoms the Israelites defeated. Every commentary and scholarly work I have read seems to miss the significance of the term translated “formerly.” The enormous city of Greater Hazor (some 140 acres) had apparently been the head of all the kingdoms (i.e., those allied against Joshua) in former times, but not in the time of Joshua. In view of its size and economic preeminence among the towns in northern Canaan that leadership role seems plausible in the 13th century BC and before (according to Egypt’s good pleasure). But, in the time of Joshua’s attack on Hazor, that preeminence no longer existed because Greater Hazor had been destroyed a century earlier.

There is another clue within the Bible’s account of Joshua’s defeat of Hazor that seems to moderate Joshua’s achievement in overthrowing the site: it is the lack of hyperbole in the record of the victory. Had Joshua destroyed Greater Hazor of some 140 acres, the largest city in ancient Canaan, the significance of this achievement would surely have been described with far greater emphasis.

Given the consistent use of hyperbole in the account of Joshua’s victories little is said of his destruction of whatever lay atop the ruins of the upper mound.[2] The text simply says: And Joshua turned back at that time and captured Hazor and struck its king with the sword, for Hazor formerly was the head of all those kingdoms. And they struck with the sword all who were in it, devoting them to destruction; there was none left that breathed. And he burned Hazor with fire (Josh.11:10–11). (Emphasis added.)

Greater Hazor (in dark gray) overlain with meager remains Joshua may have destroyed c. 1135 BC (Stratum XII/XI [consisting of pits and the lines of a few buildings]). (The dating of XII/XI is uncertain.)

(Used by permission of A. Ben-Tor and the Israel Exploration Society.)

Greater Hazor (in dark gray) overlain with meager remains Joshua may have destroyed c. 1135 BC (Stratum XII/XI [consisting of pits and the lines of a few buildings]). (The dating of XII/XI is uncertain.)

(Used by permission of A. Ben-Tor and the Israel Exploration Society.)

The Role of Jabin, King of Hazor

c. 1135-1130 BC

The name Jabin appears as king of Hazor in the northern Conquest account and in the time of Deborah and Barak in the period of the Judges. In both periods (according to the chronology here) Hazor must have been a ruin, having been destroyed a century before the Israelites arrived in the highlands c. 1135 BC.

The name Jabin may have been a dynastic name like Ramesses (of which there were eleven).[3] It is unlikely that Jabin I (in the time of Joshua) and Jabin II (in the time of Deborah) were the same individual.[4]

The leadership role of the king of Hazor in these accounts (Joshua and Judges) may have resulted from the hereditary preeminence of the kings of Hazor in former times. The heir of this title may have had the credentials to assemble such a coalition from lands that may have once been under Hazor’s influence. Jabin (I) may have claimed the ancestral authority that once attached to the ruins of the city. This is, of course, speculation.

In Kenneth Kitchen’s view, Jabin (II) in the time of Deborah, may have reigned from another (unknown) location in Galilee while keeping the style of king of the territory around the ruins of Hazor. In this way Kitchen accounts for the absence of robust archaeological evidence for occupation of the Hazor site in the time of Deborah.[5] The same argument can be made for Hazor in the time of Joshua.

Jabin I’s presence at the ruins of the Hazor mound in the latter 12th century BC (Joshua’s time) may have consisted of a temporary military encampment. The only archaeological evidence on the upper mound that may date to the 12th century BC are scattered lines of stones, pits, and other materials consistent with highlands Settlement sites (but even the dating of this Stratum XII/XI is not secure). There is no indication in the Joshua account that the site that comprised Hazor was fortified; based on the absence of hyperbole, it seems the defenders were not capable of mounting significant resistance to the Israelites.

It has been the absence of imposing archaeological structures on the mound in the latter 12th century BC that has been a principal argument against the 12th century chronology. However, the weight of that argument is minimal considering the total weight of evidence against a 13th century BC Conquest (or earlier) that includes archaeological evidence at northern campaign sites such as Taanach and Tirzah. Both sites support a Joshua campaign in the latter 12th century BC.

______________________________

[1] Some have claimed that the defacement or battering of cultic images that appear in Greater Hazor’s destruction level points to the Israelites as the iconoclasts. But this action was not unique to the Israelites. Defacement of cultic images that were not carried off from conquered towns was believed to ensure that the associated god would leave the image and thus abandon the people who had worshipped the god. The point was to demonstrate that the god(s) of the victors was stronger than god(s) of the defeated.

[2] A. Ben-Tor’s measurement. Y. Yadin et al. (1958: 1–3) claims 180-acres total (Upper and Lower Cities). Sometimes the site is said to cover 200 acres.

[3] The Akkadian equivalent of “Jabin” (Ibni-Addu) is mentioned in Mari documents nearly 600 years earlier. See A. Ben-Tor (2016: 143) and K. Kitchen (2003: 213).

[4] K. Kitchen (2003: 213) identifies the two Jabins as I and II.

[5] K. Kitchen (2003a: 213).