Biblical Hermeneutics

What is biblical hermeneutics?

The study and application of principles necessary to correctly interpret the meaning of Bible passages. While exegesis focuses on the meaning of a specific text, hermeneutics deals with principles that apply to all texts.

- There are several different types of biblical hermeneutics, based on interpretive assumptions about the Bible. The focus here is on the plain (“literal”) meaning of biblical texts.

- The primary concern of this hermeneuctic is to identify what the author meant (and his audience understood) when he wrote the text. That is the true meaning of the text.

- Paul’s admonition to Timothy (2 Tim. 2:15) explains why it is so important to discover the correct meaning of a text.

- Wesleyan University reports that there are 33,089 Christian denominations (2024). What distinguishes most of these from one another are differing interpretations of select biblical texts often based on faulty hermeneutical principles. Often these positions require marginalization of contradictory texts.

What is the most important principle?

The meaning of any passage is what it meant to the original audience (i.e., the meaning intended by the author).

Conservatives believe the text of the Bible is the product of a collaboration by God (who provided the inspiration) and the human writer (who used his vocabulary, worldview, and limited understanding of the natural order to describe events revealed to him by God).

In some cases, we must regress to the author’s understanding of the natural order and then-prevailing literary genre expectations to correctly understand (in our time) what the author intended in his time.

Conviction regarding the authority of the biblical text as an objective source of divine communication must accept that God has condescended to speak to humanity in the vernacular of the original human author and his audience. In so doing, God has appropriated concepts and prevailing beliefs of the original audience to bear profound truths of far deeper significance than our evolving (“scienftific”) understanding of the natural order.

An Example of how NOT to interpret biblical texts:

We must not assume that our meaning of a word or concept was what the original audience understood by that term. For example, our concept of “earth” is radically different from what the recorder of the earliest texts of Genesis meant by that word. We intuitively think of a planet but the author understood this term to refer to dry ground (in contrast to water/sky). Consider the flood account (Gen. 6–8):

-

- The one who recorded this event observed it from the deck of a barge. From his point of view (POV) all the earth (dry ground) was covered with water. Since he believed in a flat earth, he could only mean that all the ground to his horizon was covered with water.

- If we do not have his POV in mind we may incorrectly project our meaning and surmise that he was referring to a planetary inundation. The consequences of such a reading is grossly at odds with the writer’s POV.

- Other problematic terms that must also be qualified by his POV are the terms “mountain” and “all life.” A chief problem for modern readers is a relentless use of hyperbole (exaggeration) expected in ancient Near Eastern literature.

- Observations of the natural order by writers of the Bible texts are not scientific but phenomenal. God was unconcerned with correcting the writers’ limited comprehension of the natural order. A scientific account is irrelevant to the text.

Another way NOT to interpret biblical texts:

It is incorrect to assume the meaning of a biblical text is what it means to me. Here’s an example of where this approach has led Generation Z:

-

- Some college kids were having a get-together to check out the Bible. They sat on couches, chairs, and on the floor, eating pizza, each reading a few lines of the parable of the woman and the lost coin from Luke 15. (It’s the story of a poor woman who lost a coin somewhere in her house.)

- According to the story, when the woman discovered the coin was missing, she abandoned other activities and concerns, lit a lamp, and began diligently sweeping under the beds and in every corner until she finally found the coin. Overjoyed, she called her friends to rejoice with her.

- The leader of the study group invited each participant to tell what the text meant to them. One young man opined that it meant we should sweep our houses more often. There were nods and murmurs of general agreement. Since that’s what it meant to him, that was as acceptable as any other meaning. Wrong!

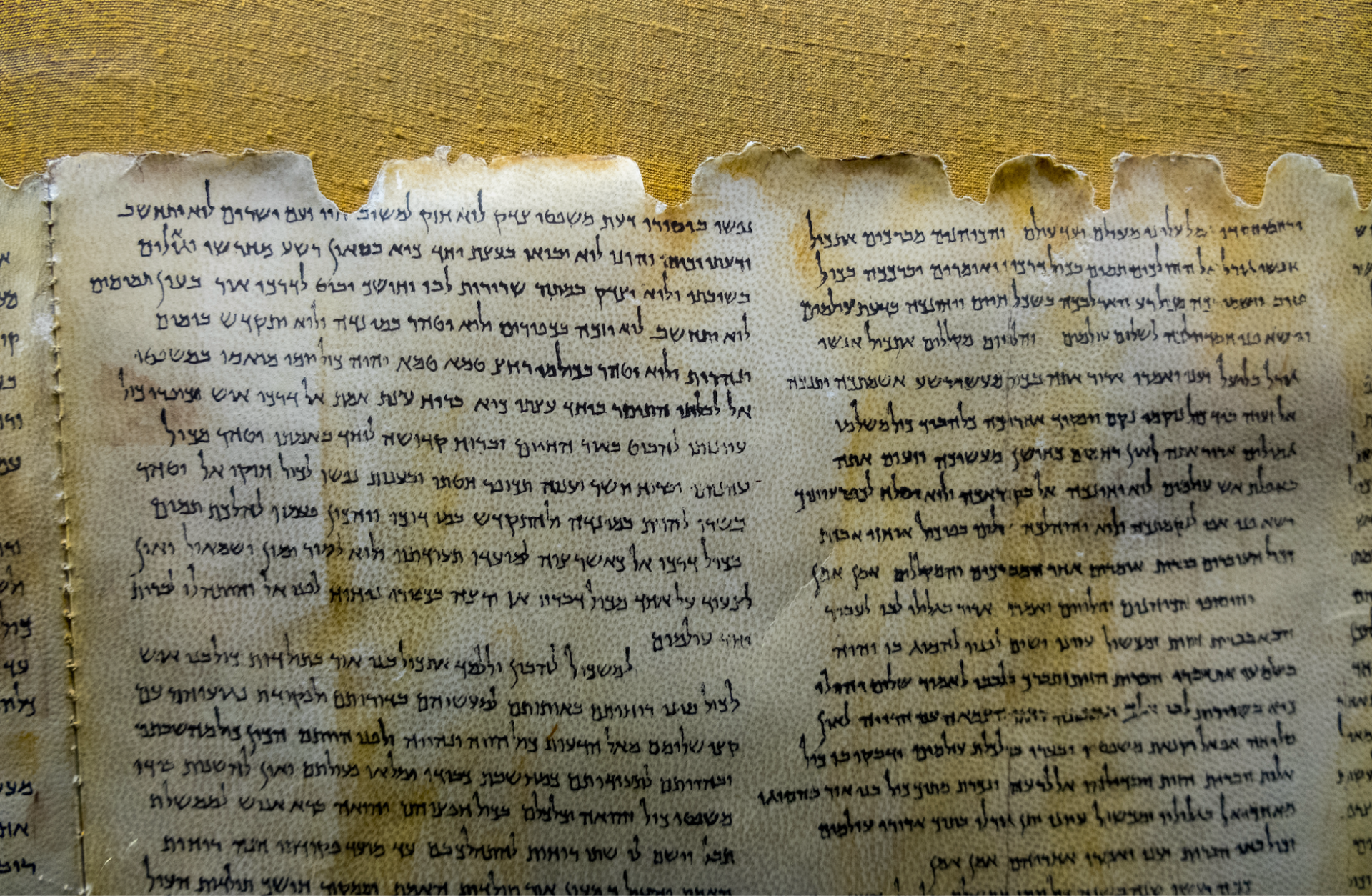

A Dead Sea Scroll

(on animal skin)

The Challenge

We must make every effort to get into the sandals of the original audience and understand what the text meant to them, not us. The deep enduring truths beneath the story are what speak to humanity throughout time.

A Dead Sea Scroll

(on animal skin)

Truths and Principles

Below are some biblical assertions about God that must underlie all interpretive principles for biblical hermeneutics to work.

Application of the principles that follow will help us find the most likely meaning of difficult Bible texts.

Biblical Truths About God

- GOD IS OMNIPOTENT

Gen. 1:1; Ps. 50:10-12; Eph. 3:8-9; Rev. 4:11.

- GOD IS OMNISCIENT

John 16:30, 21:17; Ps. 139.

- GOD IS OMNIPRESENT

Ps. 139:7–12.

- GOD HAS CREATED EVERYTHING THAT EXISTS

All that exists (except God Himself) exists in space and time (including angels); Gen. 1:1, Eph. 3:9, Rev. 4:11.

- GOD EXISTS OUTSIDE OF TIME AND SPACE

He has always existed; God (Elohim, a plurality) is Deity; all the vast ages of time are an eyeblink for the One who names himself, “I AM”—signifying existence independent of time (Gen. 1:1; John 1:1–3; Rom. 1:20). The inability of humans to comprehend the dimension Deity inhabits is the source of many misconceptions about God.

- GOD DOES NOT CHANGE

God does not change his mind or alter his course. There are some texts that state God changed his mind, that he was angry, and other expressions that are accommodations of human limitations in time. These statements are for our benefit so we can understand God’s engagement in human affairs in the stream of time; they are human imputations projected upon God because he “seems” to have changed his mind or expressed anger, etc. These anthropomorphisms cannot be literally true because they contradict non-negotiable truths about God. “He does not lie or have regret” (1 Sam. 15:29); he does not have to wait to see what a person will do though he is often portrayed as reactive to human actions—again, this is an accommodation for us so we can correlate our actions with God’s response to us (Ps. 55:19, 102:26–27; Mal. 3:6; Heb. 1:12; James 1:17).

- GOD IS GOOD

He is good in the ultimate moral sense. Only He is good. Ps. 34:48, 100:5, 145:8–9; Jer. 33:11; Nahum 1:7; Luke 18:19; Mark 10:18; 1 John 1:5. (Note: The “good” pronouncements in Gen. 1 listing of the days of creation do not refer to any moral aspect of God’s creative work; the context suggests that “good” here means his creative actions achieved what he intended.)

- GOD LOVES HUMANITY

His love for humanity has motivated every known act recorded in the Bible. Jer. 31:3; John 3:16.

- GOD DESIRES TO BE KNOWN

“Come to me” (Mt. 11:28–30), “If anyone thirsts” (John 7:37), “You will seek me and find me” (Jer. 29:13).

- GOD IS FAIR

He offers every human being the opportunity to respond to Him and to be saved (Mic. 6:8; Eze. 18:31-32, 33:11); Rom. 1:19–20 paraphrased says, what may be known about God is evident within us for God has made it evident; His eternal power and divine nature are clearly seen . . . humans who reject his overtures are without excuse. He will judge every person according to the light he/she has been given (see also Rom. 2:6-8, 14–16; 2:26–29; 5:13); people in every time and culture can be saved whether they have heard the Gospel or not. But all who are saved (past, present, future) are, will, and have been saved through the cross alone. See Rom. 3:21–30, 4:3, 15, 5:13, 20-21.

- GOD HAS NOT CREATED ANYONE FOR DESTRUCTION

Passages that suggest otherwise must be understood in context and from the perspective of the human writer/audience who must account for God’s foreknowledge. Because God knows the destiny of a person does not determine that person’s choice to reject or accept God’s offer of life. To suggest otherwise violates a non-negotiable truth about God: That he is fair and disposed to grace above justice for those who will receive what he offers them (life); he wills that none be lost. See 1 Tim. 2:4; 2 Peter 3:9; but compare Rom. 8:28–30, 9:18 where these passages would suggest God overrules human free will—which is not the case. Context does show that God “hardens” whom he wills after the individual has irrevocably turned his back to God.

- GOD WILL NOT OVERRIDE A PERSON’S FREE WILL

God will not overpower nor deny a person the exercise of his free will to accept or reject the offer of salvation. The Bible is an appeal; God continually holds out his arms to humanity asking “why will you die?” See John 1:11–12, 3:16; Eze. 18:31–32, 33:11.

- GOD MAY GIVE UP ON A PERSON AT A CERTAIN POINT

There is a point in peoples’ lives (known only to God) when God will no longer contend with them because that person (apparently) is beyond redemption (known only to God). See Gen. 6:3; Mt. 7:6; Rom. 1:24–28.

- NO ONE CAN COME TO CHRIST UNLESS GOD DRAWS THAT PERSON

Not everyone is invited to eternal life (see above point and Mt. 7:6; Rom. 1:28). Only those who, through their own volition, will listen to God will receive the invitation (John 6:44). “He who has ears” is invited/called (Deut. 29:4; Jer. 25:4; Luke 8:8). But not all who are invited will accept the invitation; many are called but few are chosen (Mt. 22:14). Jesus says, “All that the Father gives me will come to me,” John 6:37. This is not determinative, but foreknown on God’s part.

- CHRIST IS THE ONLY WAY TO ETERNAL LIFE

No one can come to the Father except through Christ (John 14:6). It is by grace we are saved through faith (Eph. 2:8)—and even saving faith is a gift of God. Abraham believed God, and it was counted to him as righteousness (Rom. 4:3; James 2:23). Saving faith may occur without having heard of Christ, but, again, all who have been or ever will be saved are saved because of Christ’s work on the cross—there is no other provision for the elimination of sin from a human resume. Sin is the issue that alienates humanity from his Creator.

- GOD HAS ALLOWED EVIL TO EXIST IN ORDER TO ACCOMPLISH HIS PURPOSES

God did not create evil. It emerged from the exercise of free will by angels and humans. Even so, evil always and inadvertently accomplishes God’s purpose. Without the existence of evil God’s full range of virtues can never be known by man or the angels. Consider the counterpoint of all things and virtues we know as good. Without the extreme contrast we could not appreciate the extraordinary goodness of God. We are necessarily “like him” because we know the difference between good and evil (Gen. 3:5, 22). As a result, we have become responsible for our actions. See Exod. 32:14; 1 Sam. 15:35; Amos 7:3; Jer. 27;19. Ironically, there is no inherent virtue in “innocence.”

- GOD DOES NOT LIE

God has not deceived humankind though he may allow some to be deceived (Num. 23:19; 1 Sam. 15:29; 1 Kgs. 22:22/ 2 Chron. 18:21; Rom. 1:24–28). For those who have definitively rejected God’s offer of life, he allows satanic deception to powerfully persuade them that a lie is truth and truth is a lie. For a terminal atheist the existence of God is unthinkable, and the very idea of God is an offense.

- BECAUSE GOD DESIRES A CERTAIN OUTCOME IN A PERSON’S LIFE DOES NOT MEAN HE SOVEREIGNLY WILLS IT TO OCCUR (see #12 above)

God does not want anyone to be lost (2 Pet. 3:9); most humans, nevertheless, will reject God’s offer and be lost (by their choice); he has given us the right to refuse his appeals (Mt. 7:13–14). It is said that those who will inhabit hell would not choose to leave to be in God’s presence; their hatred for God is all consuming, the most self-destructive of motivations.

Hermeneutical Principles

1. ALL TRUTH IS GOD’S TRUTH.

Whatever is true is true because God made it that way (science and the Bible are not in conflict as some claim).

2. SCRIPTURE INTERPRETS SCRIPTURE

The truth of one text will not contradict another when the context of both passages and the author’s intent is understood. The Bible contains a system of interlocking truths that progressively build from the creation account (Genesis) to the end of time (Revelation).

3. THE ENTIRE BIBLICAL TEXT IS AUTHORITATIVE AS GOD’S WORD TO MAN

Conservative biblical hermeneutics is based upon the assumption that it is all “God-breathed” (2 Tim. 3:16) and consistent throughout. (The theological term “inerrancy” is a mine field of rationalization; it is better to describe the Bible as the authoritative Word of God.) A believer has the inner witness, a self-attesting conviction, that God has superintended the authoring and preservation of the biblical text through the ages. This conviction is fundamental to a genuine relationship with God. The Bible is the only authoritative source of information from God that qualifies, explains, and constrains our otherwise subjective experiences of God.

- THE MEANING OF A BIBLICAL TEXT IS WHAT IT MEANT TO THE ORIGINAL AUDIENCE

“While the text is written FOR us, it was not written TO us” (John Walton.)

This often-quoted statement by John Walton has to be qualified since the text is written to us. Walton’s point is that God spoke to the people through prophets in successive times using the prophet’s then-current language, cultural practices, literary expressions, and beliefs about the nature of the physical world that are foreign to us. We must therefore understand the context of the writer and his audience lest we project inappropriate meaning to texts.

The biblical texts—in dealing with the natural order— reflect the narrow geographic and “scientific” knowledge of the human author and his audience at the time of its composition. The text does not reference nor assume a knowledge of continental, oceanic, planetary, or cosmological concepts on the part of the human author or audience. There are no “codes” within the Bible wherein hidden meaning awaits decipherment. The only texts beyond understanding of the original audience are prophetic pronouncements that allude to humanly unimagined future realities.

- HUMAN AUTHORS HUMANIZED GOD

God permitted inspired writers to speak of himself as though he were like us, bound in time and space and similarly motivated. In some contexts, this humanizing language implies limitations on God that do not exist. These theological “errors” become apparent when they contradict “non-negotiable” truths about God (above). But these “humanized” characterizations serve God’s purpose by helping us to process his apparent time-dependent response to our behavior so that we can see the cause and effect of our actions. Two of the dominant categories of human rationality are cause and effect and a moral compass. It is by these self-attesting intuitive principles that we know God exists, that he is a moral being, and that he is accessible.

- THE BIBLE DOES NOT DESCRIBE THE WORLD IN SCIENTIFIC TERMS

Physical descriptions of the natural world in biblical texts reflect the beliefs of the audience at the time of the revelation (see #4 above). This does not imply a divine endorsement of ancient non-scientific views about the nature of the world. The Bible employs only “phenomenal” descriptions of the natural order as understood by the writer and his immediate audience. At no time in history have human scientific descriptions of the universe reached a definitive state of understanding.

- AUTHORIAL INTENT DETERMINES MEANING, NOT READER RESPONSE

What the author intended is the text’s meaning. What a text “means to us” may not be the intended meaning of a text.

- WHAT A TEXT SAYS MAY NOT BE WHAT IT MEANS

To determine the meaning of a text, the reader must understand the context, he/she must identify the author’s intent, recognize the point of view of the author/speaker, be acquainted with the characteristics of the type of literature (“genre”) of the text, and correctly recognize figures of speech; application of all of these insights may be necessary to identify the meaning behind the literal wording of a passage. Gross distortions (called “letterism”) can result if these principles are not applied to difficult texts. An example of letterism is John 3:4, “How can a man be born [again] when he is old? Can he enter a second time into his mother’s womb?”

- POINT OF VIEW (POV)

The reader must identify the author’s POV of a text and avoid inappropriately imposing our understanding of a word upon the writer’s use of that word. (See #4 above.) We must ask, “Who is the author/speaker, and what does he know about what he is describing?”

- IDENTIFY AND ACCOMMODATE FIGURES OF SPEECH (FOS)

Unrecognized figures of speech will sometimes confuse the reader who thinks he/she is reading a literal description when that is not the intent of the author. FOS include consistent hyperbole (very common in the Hebrew Bible). Metaphor, analogy, simile, parable, allegory, idiomatic expressions, synecdoche, and others are abundant. We can generally identify and accommodate these intuitively but if we do not recognize an intended FOS and assume a literal meaning we can impute a meaning to the text that was unintended by the writer.

- TYPE OF LITERATURE (GENRE)

The biblical texts are written in various stylized forms in use in ancient Near Eastern literature in the time of the human authors. These forms include narrative, law, prophecy, wisdom, genealogy, itinerary, conquest, and many others that scholars have defined. The biblical authors’ audience would have recognized and expected to hear/read truths of the text packaged in then-contemporary genre rules. For example, Joshua speaks of the defeat of an enemy (no matter how modest) claiming that he left “none that breathed.” This is boiler plate rhetoric that neither the author nor the reader/hearer would have understood as a literal claim of complete annihilation of the enemy. By accepting that genre rules imposed an embellishment on certain texts we can understand why some passages are difficult to reconcile with the physical realities of the text’s setting. (Note also that the presence of these genre features also testifies to the antiquity of the authorship of the text.)

- COPYISTS/EDITORS HAVE ALTERED SOME ORIGINAL TEXTS

In a few rare instances, an original text has been altered by a later copyist or editor and survived into modern editions. An example is an ending of Mark that some translators incorporate in their editions. This passage deals with snake handling and drinking of poison (16:9–20); the earliest copies of Mark do not include this passage.

Most alterations of an original text are obvious (such as this passage in Mark); none are doctrinally critical. There are many anachronisms in the Hebrew Bible that constitute altered texts that do not affect the meaning. Anachronisms illustrate an aspect of the transmission of the text by the author or successive copyists. For instance, later copyists in some cases have updated the place names of a long-forgotten locations for the benefit of their current audience.

And then there is a more serious consideration: There are two possible examples of later editors/copyists adding or altering an original text for other reasons. These two instances have created much confusion for later readers. One is the vast numbers (“millions”) of the Israelites in the Exodus. This error is the result of reading back into an original text a later definition of the term ‘eleph translated in later times as literally “thousand”.

But this change carried forward into translations cannot be the meaning intended by the authors of several original texts where this term appears. (See a blog article on this subject elsewhere on this site.)

A second possible editorial insertion is 1 Kgs. 6:1 that claims that Solomon began construction of the temple in the 480th year after the Israelite Exodus; this insertion was apparently added to embellish the ironic significance of the occasion. On what basis can we consider this an editorial addition to the original text? Because this statement is irreconcilable with other texts (e.g., Exod. 1:11); see principle #2 above. Beyond this, if this text is accepted as original we must conclude that the story of Israel’s origins is a human invention. Why? Because there is now a large body evidence showing that this chronology (based on this verse) is contradicted at every site/event after the Exodus.

This single passage is one of the chief obstacles to the reconciliation of the Bible’s story of Israel’s origins with the historical reality of the Late Bronze/Iron I Age (c. 1550–1000 BC).

- CONTEXT DETERMINES MEANING

Nothing is more important in determining the meaning of a Bible passage than context. Some concepts and declarations can be understood only by knowing what the author/audience understood by the reference—given their historical, cultural, geographic, theological, and other life perspectives. Context is found within a sentence which in turn is determined by the paragraph, the chapter, the book, the Testament, and the whole Bible.