The Merenptah Stele and the Origins of Ancient Israel

The first and strongest argument against a 12th century BC Israelite Exodus/Conquest is the hundred-year-old interpretation of the Merenptah Stele’s reference to Israel.[1] In this text Pharaoh Merenptah (1213–1203 BC) claims to have destroyed the seed of Israel. The appearance of the term for Israel in the Stele’s text is the first and only known—and generally accepted—reference to the Israelites ever found in ancient Egyptian records. The burning question is: Where were the Israelites when Merenptah destroyed their seed?

Virtually all scholars believe there are clues within the Stele that intend to locate the Israelites in Canaan (or the Transjordan) when Merenptah “destroyed their seed.” If true, this should have happened sometime before c. 1208 BC. But there are a number of reasons why this cannot be correct.

As this article will show, the Stele’s reference to Israel can also be interpreted to locate the Israelites in the Egyptian Delta at the time of Merenptah’s assault. The credibility of the Bible story of Israel’s origins is at stake: if the Israelites were in Canaan in this period – as the traditional interpretation insists – the Exodus had already occurred and the archaeological evidence cannot be reconciled with any biblical event after the Exodus.

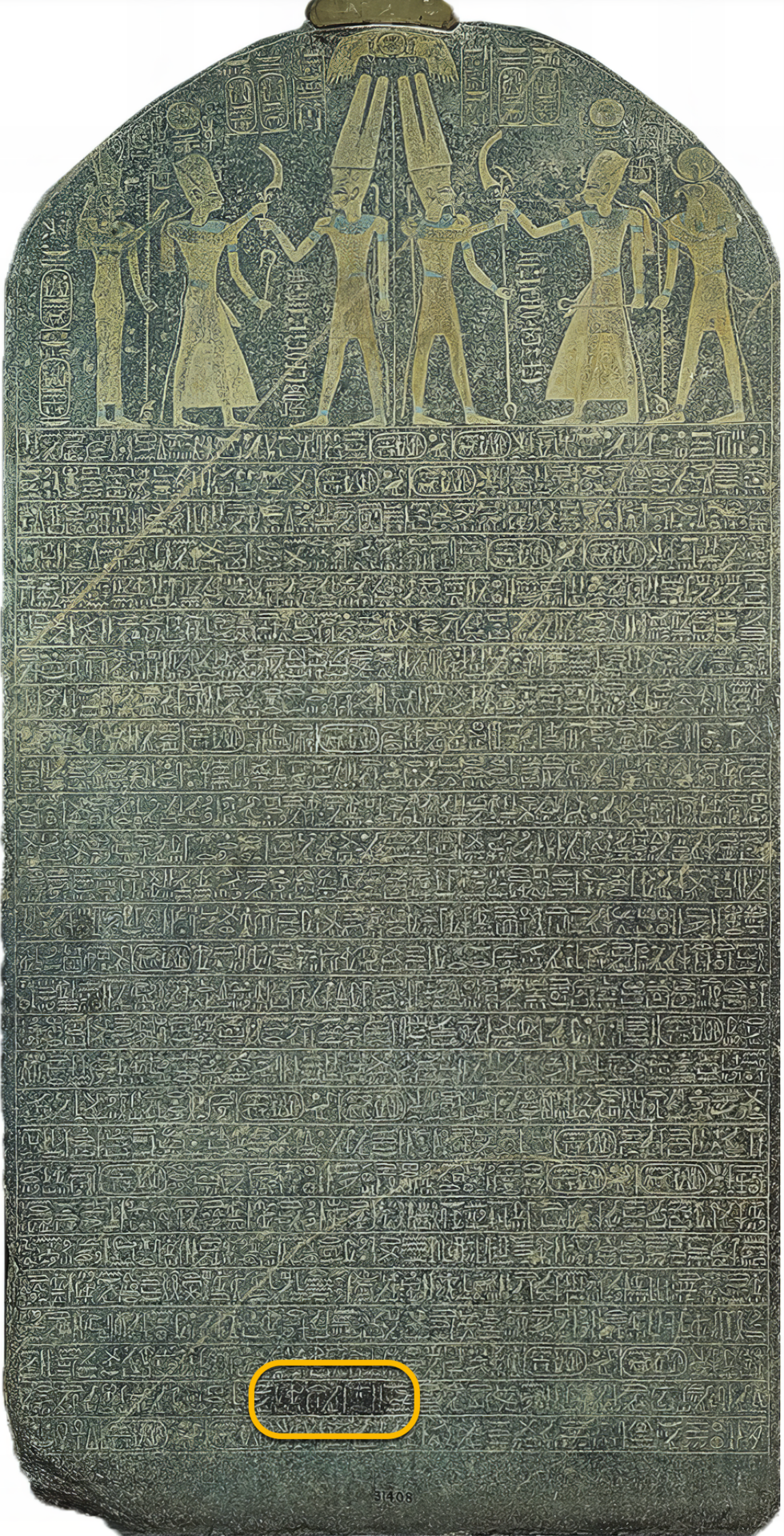

The Merenptah Stele

Highlighted area mentions Israel

(Courtesy of BiblePlaces.com)

The Merenptah Stele

Highlighted area mentions Israel

(Courtesy of BiblePlaces.com)

The first and strongest argument against a 12th century BC Israelite Exodus/Conquest is the hundred-year-old interpretation of the Merenptah Stele’s reference to Israel.[1] In this text Pharaoh Merenptah (1213–1203 BC) claims to have destroyed the seed of Israel. The appearance of the term for Israel in the Stele’s text is the first and only known—and generally accepted—reference to the Israelites ever found in ancient Egyptian records. The burning question is: Where were the Israelites when Merenptah destroyed their seed?

Virtually all scholars believe there are clues within the Stele that intend to locate the Israelites in Canaan (or the Transjordan) when Merenptah “destroyed their seed.” This should have happened sometime before c. 1208 BC. There are a number of reasons why this cannot be correct.

As this article will show, the Stele’s reference to Israel can also be interpreted to locate the Israelites in the Egyptian Delta at the time of Merenptah’s assault. The credibility of the Bible story of Israel’s origins is at stake: if the Israelites were in Canaan in this period – as the traditional interpretation insists – the Exodus had already occurred and the archaeological evidence cannot be reconciled with any biblical event after the Exodus.

The Text of Merenptah’s Stele

The last two lines of the Stele (in hieroglyphic text) are the most important for our purposes. They read:

The (foreign) chieftains lie prostrate, saying “Peace”. Not one lifts his head among the Nine Bows. Libya is captured, while Hatti is pacified. Canaan is plundered, Ashkelon is carried off, and Gezer is captured. Yenoam is made into non-existence; Israel is wasted, its seed is not; and Hurru is become a widow because of Egypt. All lands united themselves in peace. Those who went about are subdued by the king of Upper and Lower Egypt … Merneptah.[1] (Emphasis added.)

Interpreting the Stele’s Text

What is the Stele?

A ten-foot-tall black granite slab engraved with hieroglyphics discovered in 1896 by William Flinders Petrie in the ruins of the funerary temple of Pharaoh Merenptah.[2] This ruin lies amid the remains of other funerary temples of pharaohs of the New Kingdom on the edge of the western desert, three miles across the Nile from the Karnak Temple complex at Thebes. Merenptah commissioned the stele to record notable deeds of his reign that commended him to the gods and to the people.

What does it say?

The main subject of the text (28 lines) is Merenptah’s military victory over a coalition of Libyans and Sea People in the western Delta that occurred c. 1208 BC. His notable victory preserved the sovereignty of Egypt.

A secondary subject of the Stele is an earlier military campaign that Merenptah (apparently) conducted into Canaan. During that campaign he claims to have assaulted several vassal towns in Canaan/Transjordan and destroyed the town of Yenoam. At issue is whether, on this same campaign, he also destroyed the seed of Israel.

Why do scholars believe it locates the Israelites in Canaan?

First: The hieroglyphic symbol meaning “foreign” (the throwing stick) associated with the Israel term, is commonly thought to mean the Israelites were not physically located in Egypt; the absence of another symbol (mountain symbol) means the Israelites had no land of their own.

Second: Scholars believe the chiastic arrangement of a series of toponyms (peoples/cities/lands) in the final lines of the Stele (that include the Israelites) implies they were in Canaan.

Neither argument bears sufficient rationale to locate the Israelites in Canaan, especially in consideration of the consequences and much circumstantial evidence to the contrary.

Why traditional interpretations of the hieroglyphic text cannot be correct

The Linguistic Argument

It is commonly believed that the “foreign” classifier (modifying Israel) does not appear in Egyptian texts when referring to Asiatics who came to Egypt to become part of the culture. By extrapolation, it supposedly means the Israelites (defined by this foreign classifier in the Stele) were not physically in Egypt when Merenptah destroyed their seed.

However, the foreign symbol is an appropriate modifier for pastoral sojourners (Shasu) who entered the Wadi Tumilat to sustain their animals in time of drought. These Asiatics had no intention of residing permanently in Egypt nor interest in being assimilated into Egyptian culture. The Israelites fall into this category.

They entered the Egyptian Wadi Tumilat as foreigners. They were enslaved (c. 1570 BC) and remained foreigners beyond assimilation. They were also foreigners by location: The area in the eastern Delta that the Israelites inhabited was designated as a “foreign” land (throwing stick and mountain symbol) even though this frontier region (Goshen/Tjeku/Succoth/Wadi Tumilat) was inside the Walls of the Ruler and garrisoned by Egyptian troops in (possibly two) fortresses. There seems no more appropriate way for Merenptah’s scribes to define the Israelites than landless foreigners within Egypt’s eastern frontier.

The Literary Argument

The literary argument is based on the chiastic arrangement of several toponyms that include the Israelites in the list. But there is no consensus among scholars establishing how Israel is supposed to relate to the other toponyms.

I believe the Israel term is paired with the term for Canaan (Kurru) in a near-far relationship that accommodates the Israelite presence in Egypt.

In any case, there is insufficient evidence within the linguistic and literary arguments to justify the enormous consequences for biblical historicity and the archaeological evidence if the Israelites actually were in Canaan in the time of Merenptah.

Why the Israelites had to be in Egypt during the time of Merenptah

As noted above, if the Israelites had been in Canaan in the time of Merenptah, the Exodus would have already occurred in the reign of Merenptah’s father, Ramesses II (1279 – 1213 BC). This sequence assumes Exod. 1:11 is historically accurate in identifying Ramesses II as the Pharoah of the Oppression; it was evidently under his regime that the Israelites built the store cities Pithom and Raamses (Pi-Ramesses), cities known to have been built by Ramesses II.

It follows that Moses grew up in the house of Ramesses II as a minor personality among many others being trained in the various palaces. Contrary to the imaginative tale of Josephus, Moses was not in the succession for the throne since Ramesses had a multitude of heirs. Though privileged, Moses’s destiny changed when he murdered an Egyptian task master and fled for his life. This happened in the reign of Ramesses II.

Because the traditional interpretation of the Merenptah Stele places the Israelites in Canaan during Merenptah’s reign, advocates of the 13th century chronology reason that the Exodus must also have occurred in the reign of Ramesses II for the Israelites to be in Canaan in the early years of Merenptah’s reign (Ramesses’s successor).

They conclude that Ramesses II was both the Pharoah of the Oppression and the Pharaoh of the Exodus. But that deduction ignores Exod. 2:23 and 4:19 which state that Moses did not return to Egypt to lead the Exodus until after the death of Ramesses II (and presumably after a change of regime/dynasty).

If the Exodus occurred during Ramesses II’s reign, the Israelites would have arrived in Canaan in the second half of the 13th century BC. In addition to the contradictions within the biblical text, archaeological evidence at a dozen biblical sites render this interpretation impossible. Towns the Israelites supposedly encountered/destroyed in the Negev/Arabah, the Transjordan, and Canaan did not yet exist in that period.

There is other evidence that the Israelites could not have been in Canaan in the time of Merenptah. During the allotment of the tribal lands at the beginning of the period of the Judges (1130 BC), there is a boundary marker between the tribal allotments of Judah and Benjamin called “the waters of Nephtoah” (Josh. 15:9, 18:15). The “waters of Nephtoah” means the “spring of Merenptah”; it refers to a spring in the northwest suburbs of modern Jerusalem that appears to have been a waypoint on Merenptah’s campaign to destroy the town of Yenoam (mentioned in the Stele). This spring of Merenptah—known before the Conquest occurred—requires that Merenptah’s campaign into Canaan must occurred before the Israelites appeared in Canaan. Assuming this is not an anachronism, the Exodus had to have occurred sometime after the reign of Merenptah.

Why is Merenptah’s slaughter of the Israelites not mentioned in the Bible?

Another problem with assuming the Israelites were in Canaan in the time of Merenptah rather than in Egypt, is the absence of any mention of Merenptah’s assault on the Israelites in the Bible. The best explanation for this is that Merenptah’s action against Israel occurred in the Egyptian Delta while Moses was in Midian.

When Merenptah moved all of his troops to the western Delta, the Israelites (apparently) attempted to escape Egypt.

When Merenptah emptied all his garrisons of troops and proceeded west to engage the massive invasion force of the Libyans and Sea Peoples in the western Delta c. 1208 BC, the Israelites unsuccessfully attempted to escape Egypt. In this scenario, the Stele has recorded Merenptah’s retribution.

There is, I believe, a telescoped reference to this escape attempt in Exod. 2:23-25. Ramesses II, at the beginning of the Oppression, proclaimed: “Behold, the people of Israel are too many and too mighty for us. Come, let us deal shrewdly with them, lest they multiply, and if war breaks out, they join our enemies and fight against us and escape from the land” (NASB). This fear, expressed by Ramesses II, was realized in the reign of Merenptah during the time of his war against the Libyans and Sea Peoples.

The point of view of the book of Exodus (and subsequent texts in the Pentateuch) is that of Moses (the presumed author). Moses, while in Midian, was not witness to Israel’s escape attempt in the time of Merenptah (though Exod. 2:23-25 may allude to this). Moses had no real-time knowledge of this disastrous event and, therefore, did not record it. This is the only explanation that reconciles Merenptah’s reference to Israel with the archaeological evidence and preserves the integrity of the biblical text. Also, it is the only explanation that makes sense of the archaeological evidence supporting biblial events that must have occurred in the 12th century BC.

[1] Translation by J. Hoffmeier (2000b: 41). The Stele has 28 lines, 23 of which describe the battle with the Libyans.

[2] The original stele was inscribed by Amenhotep III (1391–1353 BC). Merenptah (1213–1203 BC) appropriated the stone from the ruins of Amenhotep’s funerary temple and engraved the reverse side with his own text. This important artifact is also referred to as the Israel Stele and Merenptah’s Victory Stele. For an extensive discussion of this issue see The Bible and the Origins of Ancient Israel, ch. 10; or L. Bruce (2019).