Jericho: A Case Study

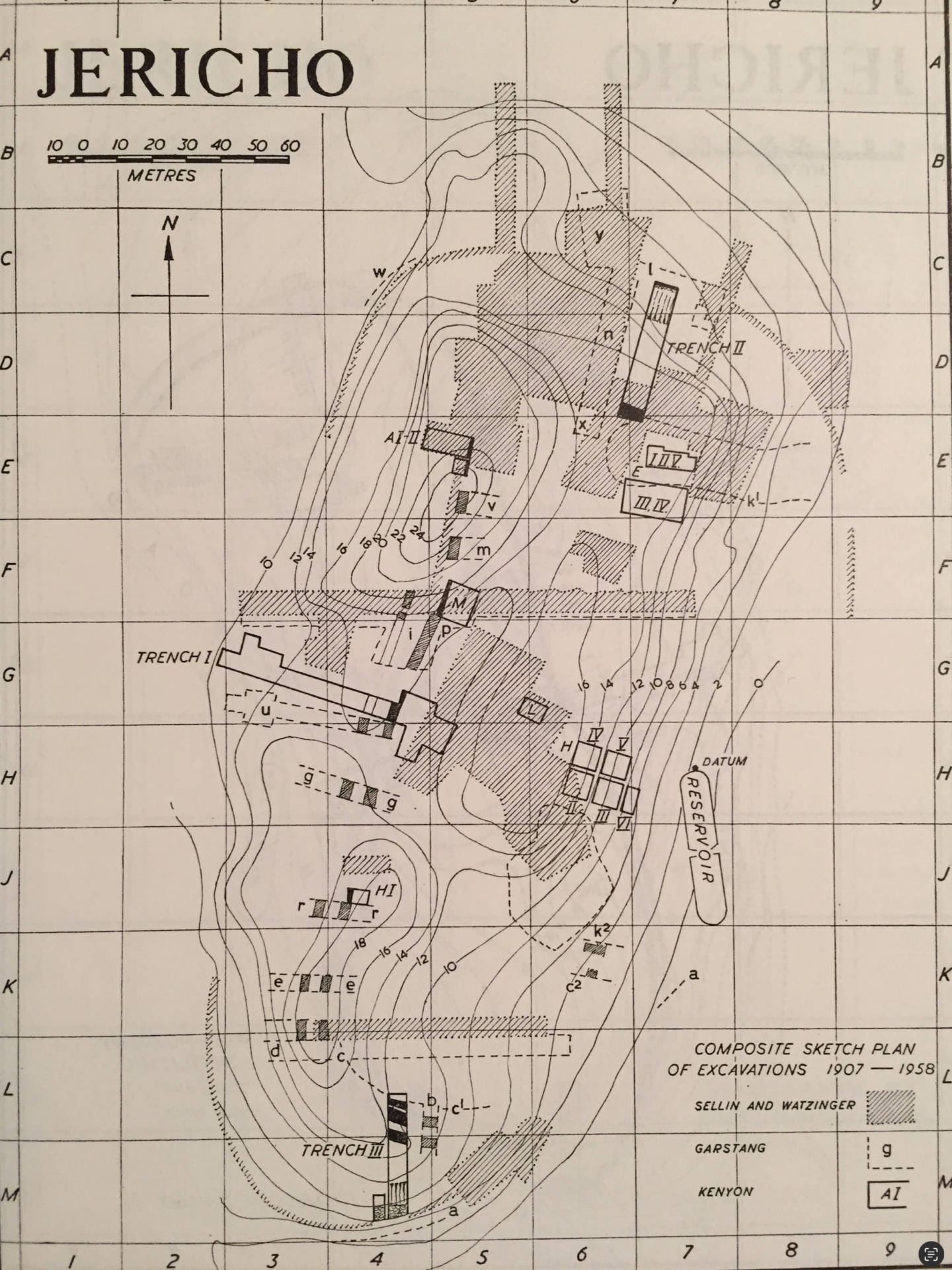

Kenyon’s Composite of Excavations (1907–1958)

The Austro-German Expedition 1907-1909

Ernst Sellin and Carl Watzinger (who excavated Jericho from 1907–1909) unwittingly recorded evidence of an Iron I occupation in their 1913 excavation report. These pioneer excavators had no grasp of the importance of meticulously identifying discrete strata of successive occupational periods. In their wide-area exposure of the central and northern part of the Jericho mound they evidently dug through the Iron II Stratum to the Iron I level in some areas, believing that what they uncovered was a single stratum built by the Israelites.

70 Years Later . . .

Almost 70 years after the Sellin-Watzinger excavation, two German scholars studying Sellin’s and Watzinger’s excavation report found a graphic depicting both Iron I and Iron II vessels. The excavators assumed these vessels came from a single Isralite occupation level. But they did not. The excavators had conflated three strata separated by hundreds of years. The Iron I material is the primary evidence of the short-lived population Joshua destroyed (in the Iron I period).

The Evidence

Traditional dates for Joshua’s destruction of Jericho (Tell es-Sultan) are c. 1406 BC and c. 1230/1220 BC. But there is no persuasive evidence of an occupation or destruction level in this period (the Late Bronze Age [1550–1200 BC]) that supports these traditional dates.

Since Kathleen Kenyon’s time (the 1950s), there has been general agreement that Tell es-Sultan was uninhabited in the 13th century BC, although Lorenzo Nigro has seen enough Late Bronze Age material in his excavations to question this assumption. Still, the only reliable evidence of a Late Bronze Age occupation stratum, that I am aware of, was a small patch of floor Kathleen Kenyon found on Spring Hill. On this floor she found a single Late Bronze Age juglet.

The presence of Late Bronze Age material does not mean the site was occupied. This may point to the site as an assembly point and burial location used by seminomadic tribal groups (similar to Arad and other sites such as Kadesh-Barnea used by the Israelites for forty years). Kenyon found 507 tombs (mostly shaft types) with multiple interments in the immediate vicinty of the mound. Much of the grave goods date to the Middle- and Late Bronze Ages. But again, there is no clear evidence of an occupation stratum. This is the reason why dating the Conquest at Jericho to the Late Bronze Age has little basis.

There is, however, evidence of an Iron I (1200–1000 BC) occupation at Tell es-Sultan that was arguably destroyed c. 1135 BC, consistent with evidence of the biblical Conquest at other sites at this time. And there is circumstantial that a mudbrick city wall fell outward and collpased against the base of the mound in this period, just as the Bible describes in the book of Joshua. This fallen wall was discovered by Kathleen Kenyon in the 1950s.

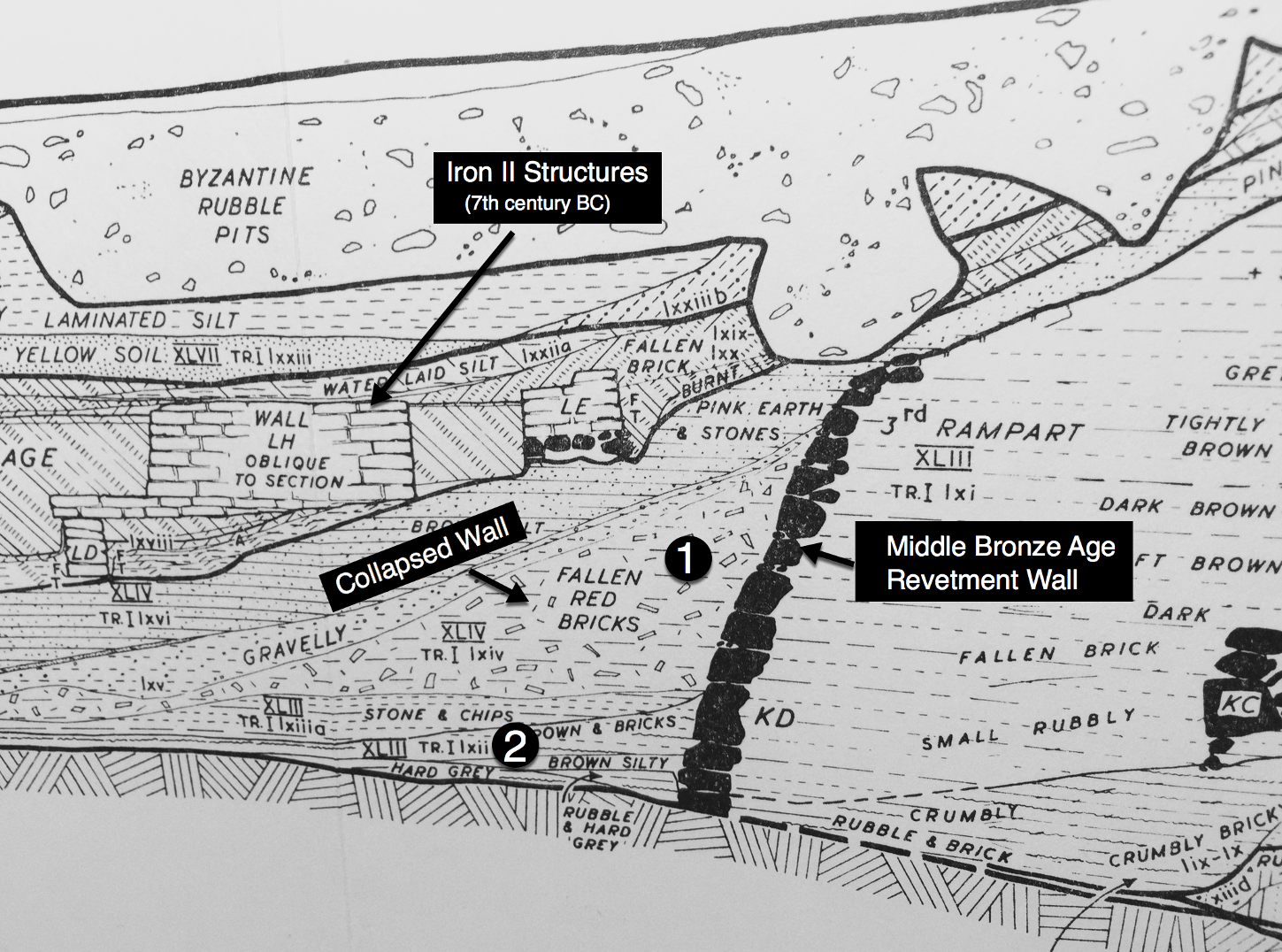

In her cross section drawing of this feature, Kenyon shows the wall overlain by deep layers of erosion material, attesting to a long period of abandonment of the site. On top of this erosion material is an Iron II reoccupation. This sequence is described in Josh. 6:24 and 1 Kgs. 16:34. If these biblical records are authentic, the last and only occupation level at Jericho that could have existed before it was abandoned for hundreds of years is that associated with the fallen wall.

Iron I and II pottery from Jericho discovered by the Sellin/Watziner Expedition (1907-1909)

Who were the people the Israelites encountered at Jericho?

The Settlement

The Iron I vessels at Tell es-Sultan testify to an occupation that may have begun shortly after c. 1200 BC; it would have endured 60 to 70 years before its destruction. It makes sense that the builders of this occupation level must have been part of the Settlement occurring throughout Canaan at the end of the Late Bronze Age.

This demographic phenomenon is evidence of the migration of populations fleeing a severe drought and destruction that brought down the Late Bronze Age civilizations in the northern Levant, Anatolia, and Greece. The relatively sudden arrival of these people of varied ethnic backgrounds explains the tripling of the population of Canaan in some areas of the highlands in the early 1100s BC.

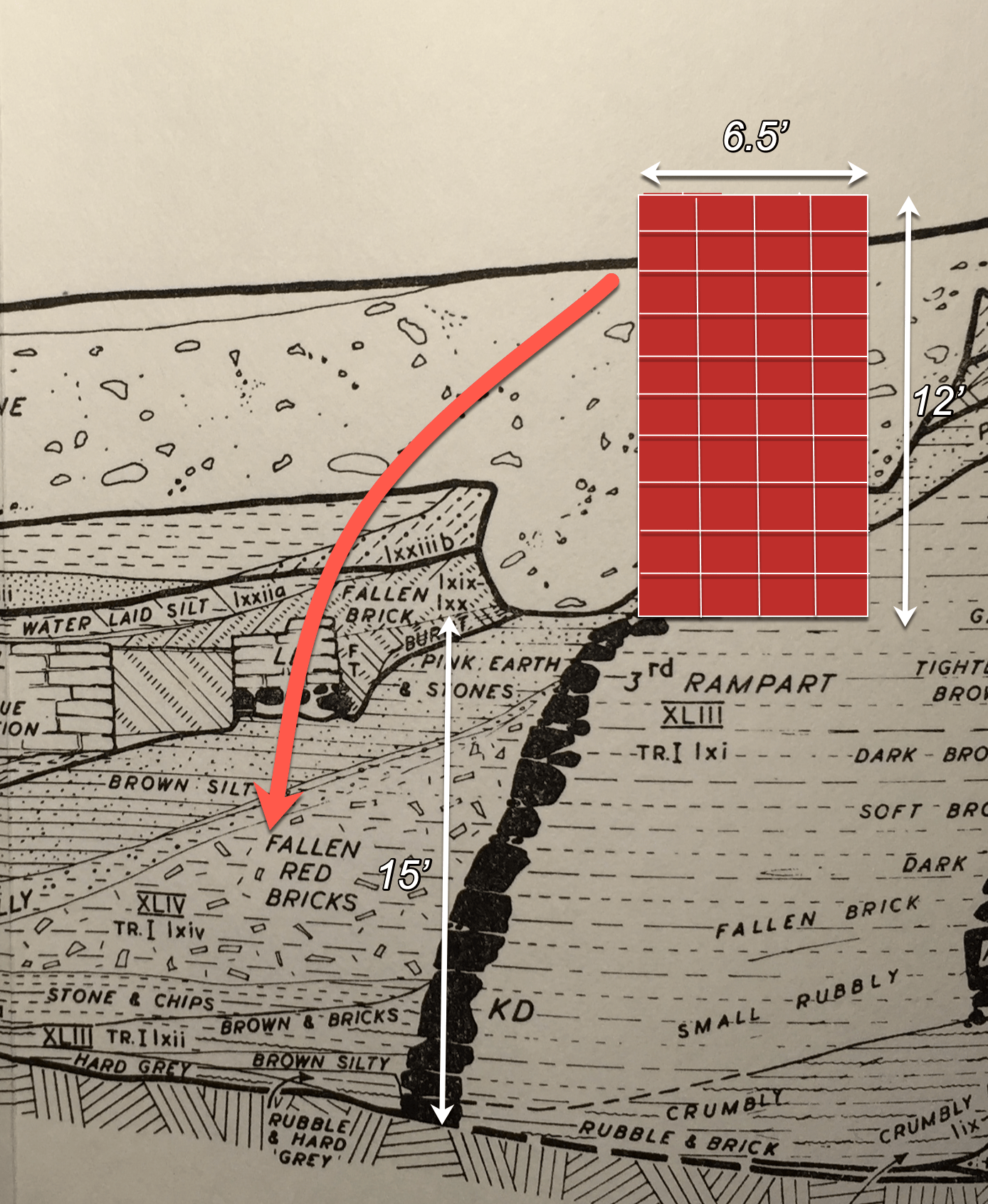

These people were of varied ethnic origins. They destroyed towns in their path and built many new ones. They reoccupied long-abandoned sites like Ai, Hebron, and (presumably) Jericho. Tell es-Sultan would have been of prime interest to these new settlers since they were obviously concerned with security. The site had ready-made defensive structures featuring a massive 15-foot high cyclopean rock revetment wall built in the Middle Bronze Age. This wall braced the enormously heavy ramparts of interleaved earth that sloped upward to the base of an upper wall. (The purpose of the ramparts was to prevent the close approach of siege engines.)

Tell es-Sultan also had a prolific spring within the eastern defensive perimeter capable of sustaining the people within the wall and supplying irrigation for the surrounding fertile fields that otherwise would revert to desert. The site was also strategically located along commercial roads.

The newly arrived Settlement people had only to clear the face of the Middle Bronze Age revetment wall down to bedrock and construct a mudbrick wall atop this structure to establish a virtually impregnable defensive system. (Kenyon calculated the size of the mudbrick wall to be 12 feet high and 6.5 feet thick, based on the volume of the mudbrick debris she identified in Trench I.)

I believe the evidence supports the conclusion that the wall the Settlement people built collapsed in an earthquake as the Israelites watched. Some five thousand Israelite soldiers then advanced into the city and set it on fire. Surveying the smoldering ruins, Joshua cursed the site and anyone who would rebuild it. It was to remain a permanent testimony to God’s judgement of the Amorite culture.

The Biblical Strata

The Bible alludes to three successive strata associated with the Joshua story: 1. The stratum Joshua destroyed (Josh. 6:26). 2. The stratum of abandonment (almost 300 years). 3. And the stratum of reoccupation in the reign of Ahab (1 Kgs. 16:34). Evidence of this sequence arguably appears in Trench I of Kathleen Kenyon’s excavation reports from the 1950s.

Trench I excavated by Kathleen Kenyon in the1950s. #1 and #2: Middle Bronze Age sherds within and below the fallen wall material.

MB, LB, and Iron Age sherds appear in the erosion above the fallen red bricks (brown silt, pink earth and stones)

Dating the Wall

The only evidence that the Israelites destroyed Jericho rests solely on whether the fallen wall was associated with Joshua’s destruction of the city and when it fell. Unfortunately, there is no definitive means of dating the life of this wall beyond a “during or after which” date established by pottery finds. The presence of datable diagnostic sherds within the matrix of the bricks of the fallen wall and within the strata that sandwich it point to a date during or after the Middle Bronze Age (2000–1550 BC). That’s not much help.

But if we grant credence to the biblical witness there is a way to use circumstantial evidence to date the wall’s collapse. The Joshua text claims that the Ai was destroyed immediately after Jericho. We have a relatively secure date for this, c. 1135 BC. The destruction of Jericho should, therefore, date to the same year, c. 1135 BC.

There are also a dozen other datable Conquest sites or events that narrowly fit this same date (documented elsewhere in the website). These contextual dates alone would seem to date the fallen wall. But again, can we be sure this wall is associated with the Conquest)? How can we know that?

The means of associating the wall with Joshua’s’ destruction of Jericho rests upon the testimony of Josh. 6:24 and 1 Kgs. 16:34. These texts identies a destruction event (the fallen wall), followed by a fallow period lasting hundreds of years, followed finally by the site’s reoccupation in the Iron II. This appears to be the sequence identifed by Kenyon in Trench I: Fallen red bricks, brown silt, Iron II structures. (This line of reasoning, however, assumes that the sequence in Kenyon’s Trench I reflects the site’s history across the tel and is not unique to this part of the mound.)

Assuming this last condition is valid, the point to take away from this sequence is that there was no occupation level between the collapsed wall and the site’s reoccupation in the 9th century BC. This assumes that Jericho (again, specifically the mound of Tell es-Sultan) remained a barren heap until the time the entry was recorded in 1 Kings. This long period of abandonment was likely common knowledge.

This deduction but makes sense of an otherwise meaningless mass of dirt and rock.